Pierre Bonnard is known to many as the ‘painter of happiness’. He created vividly colourful scenes of the French countryside as well as intimate moments he shared with both his wife and lover. They are bursting with emotion and whimsy.

The Tate Modern’s new exhibition explores his life in more complexity. Bonnard worked hard to create almost fantastical scenes of happiness and hope, but he shared his more troubled inner problems through his art as well.

He even captured some of the devastation of World War One; but the exhibit starts off on a brighter note.

It begins when he was already a well-known and established artist who had been inspired by Matisse’s bold use of colour. He started to focus less on form and more on colour and the emotion felt by viewing his work.

He also became increasingly inspired by photography for the way it could capture more honest and less rigid parts of his own life. He did not want to paint classical portraits of people posing, but instead wished to capture particularly important moments which carried a lot of weight and meaning to him.

To do this, he mostly painted from memory. He would not sit with an easel in the garden of his home in the south of France. He would instead wander about the space to gain inspiration and then paint indoors, pinning the canvas to the wall.

It sometimes took him years to finish one of his paintings as he carried them around with him from village to village. They almost took on a life of their own, slowly becoming detached from what really occurred or was seen and more focused on Bonnard’s own memory of events.

This allowed him to create work that was less structured and realistic, and his painting Summer 1917 is a prime example of this. The scene shown is that of a thick and dense garden. Shapes of children can be seen frolicking about the landscape, almost blending in with their colourful surroundings.

It is as if he has condensed an incredibly meaningful and somewhat large memory into just one frame. You can’t help but be drawn into Bonnard’s memory and feel as if you are living it with him.

The exhibition also changes things up a bit by adding in a handful of rarely shown photographs by Bonnard. These photographs are hung alongside almost 100 paintings, and explore the lesser-known area of the French artist’s practice.

It shows his personal life in an entirely different way, as it would have been seen in real life rather than memory. It contrasts perfectly with his paintings on similar subject matter.

But his paintings ooze character and life, far beyond what can be captured on film. A lot of this can also be owed to his style of brushwork. He creates a sense of perpetual movement, as if the scene is being played on a loop; the memory is alive.

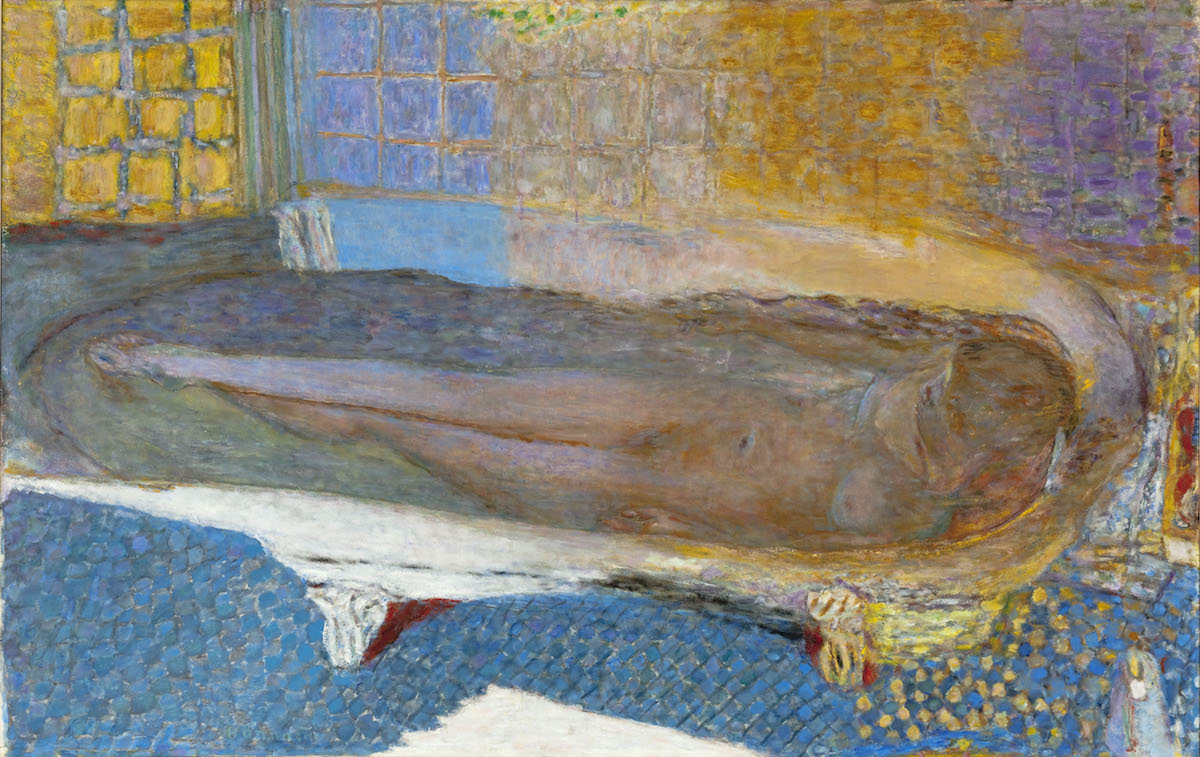

This can be seen as he captures more melancholy moments in his life. A reoccurring subject matter is his wife Marthe de Méligny, who suffered from an illness which led her to undergo hydrotherapy. She would bathe in a tub frequently.

He paints this scene over and over again. At first it seems as if he is simply showing a loving picture of his wife bathing, but it gets increasingly darker and more abstract as you move throughout the exhibit.

Nude in a Bath 1936-38 is one of the best-known versions where you can almost see the bathwater moving.

But some of the most telling paintings are Bonnard’s very own self-portraits. He looks sad and alone in each one. His face is stripped of colour, alluding to greater anxieties and inner turmoil. He is known for being the painter of happiness, but this perhaps only masked deeper issues.

He wanted to recreate joyous memories and spread feelings of hope to those who viewed his artwork. It seems as if he may have even been trying to inspire himself, too.

To bring more light and colour to his own life. To remember the good times he spent with his wife before she died. And the more peaceful existence which endured before wartime.

This new exhibit takes viewers on that very journey with Pierre Bonnard.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory is on at the Tate Modern from 23 January to 6 May.