WHEN you’re a world-renowned silversmith with a Royal Warrant and commissions from Middle Eastern monarchs, international heads of state and luxury brands, curating a snapshot of your life’s work is no easy task.

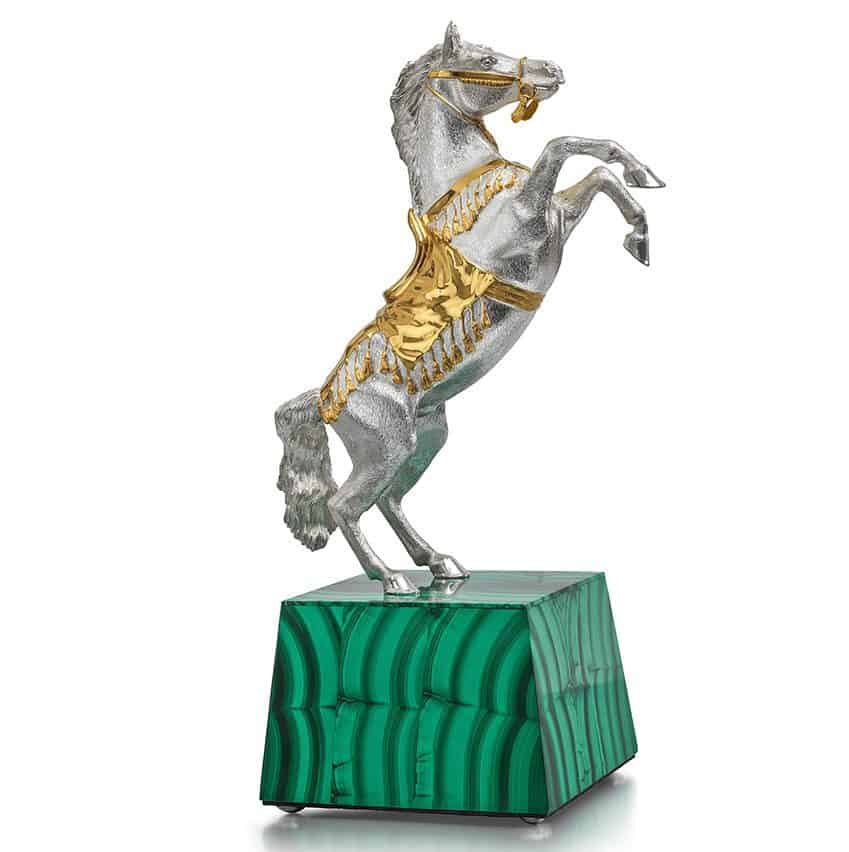

Does one go with the sterling silver rearing Arabian horse or 600-piece silver dinner set? The 18ct gold Omani khunja blade with a gem-encrusted scabbard or the silver model of an Aston Martin?

But Blackfriars-based silversmith Grant Macdonald has relished the challenge of whittling down his 50-year career to just 150 pieces for the retrospective currently on display at Goldsmith’s Hall, Grant Macdonald: International Silversmith.

“It’s been quite cathartic, I’ve come across pieces from the 1970s and ’80s that I’d completely forgotten about, but were so important to me at the time,” he says.

“I’m lucky I’m alive to do it really, if they do an exhibition like this posthumously you miss out on all the good bits.”

The “good bits” featured in the exhibition, which was co-curated by former Goldsmiths’ Company art director Rosemary Ransome Wallis, range from an 18ct gold scimitar sword embellished with rubies and diamonds right down to a simple silver chalice he made for a small church in Buckinghamshire at age 19.

“I hadn’t seen it since I sent it off in 1969,” he says of the chalice, which he managed to track down using the original job sheets tucked away in the attic of his Blackfriars workshop.

“You always hope to be reunited with these pieces at some point, particularly as they’ll probably outlive you, and I’m lucky this particular piece went to a good home; they use it every week but it still came back almost as good as it went.”

In amongst all the cavalry and cups lies a single silver spoon also of considerable significance; it was the first piece Grant ever made as a teenager while tagging along on house calls with his father, a doctor in North London. A patient showed Grant his workshop and the 14-year-old who was “never much good at anything” was hooked.

He studied at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, now Central Saint Martin’s, for a year and established his first workshop in Palmers Green before making the move to the craft heartland of Clerkenwell.

“I was in amongst all the silversmiths and clockmakers, Hatton Garden was right around the corner so you could easily nip out and get something polished or engraved – it was all on your doorstep.

“Nowadays when you send things off to be serviced or amended you miss out on the face-to-face, which is a shame – I think people still like buying from people.”

And Grant hasn’t had to travel far to find one key market for his pieces. A former master of the Worshipful Company of Barbers and prime warden of the Goldsmiths, he has become the unofficial silversmith for the City’s livery companies; crafting commemorative pieces, gifts for visiting VIPs, and shrieval chains and badges for City sheriffs.

In fact, one of the first calls an incoming sheriff will make is to Grant’s workshop where together they will peruse various heraldry and past pieces to find the right fit. Some stick with tradition; hobbies, university heraldry surrounding their own coat of arms, while others opt for a more flamboyant shape to tell their story.

There have been 36 in total (of which 20 are on display at the exhibition), however, he refuses to be drawn on picking a favourite, saying it would be like “choosing between grandchildren”.

“I’ve been very fortunate to meet most of the sheriffs since 1982 and they’re all rather spectacular people,” he says. “It has made for a very interesting group of friends.”

However, the bulk of Grant’s commissions come from well beyond the City’s walls. Buyers in the Middle East currently account for around 96% of the workshop’s output of luxury silver and gold items and has Grant on a plane to the Arabian Peninsula at least once a month. Once, it was three times in one week, but as Grant says, “you have to turn up or people will forget about you”.

Still, one imagines it would be difficult to forget the name Grant Macdonald having laid eyes on that scimitar sword, or the rearing Arabian horse, or the life-sized falcon in sterling silver that feature in the exhibition’s commissions from the Middle East.

He has come a long way from the simple silver spoon fashioned in a makeshift workshop in North London, as has the industry.

“There was huge demand for domestic silver when I was starting out in the 1970s and ’80s, and that has waned considerably,” he says.

“I think in the last few years it has become more of an art form; craftsmen and designers have reinvented themselves and their work, creating pieces that are much more bespoke and special.

“That’s how British silver still has such a great reputation internationally. The world bids a path to London’s door – we’re known for the good stuff.”

Grant Macdonald: International Silversmith is on at Goldsmiths’ Hall until 25 July.