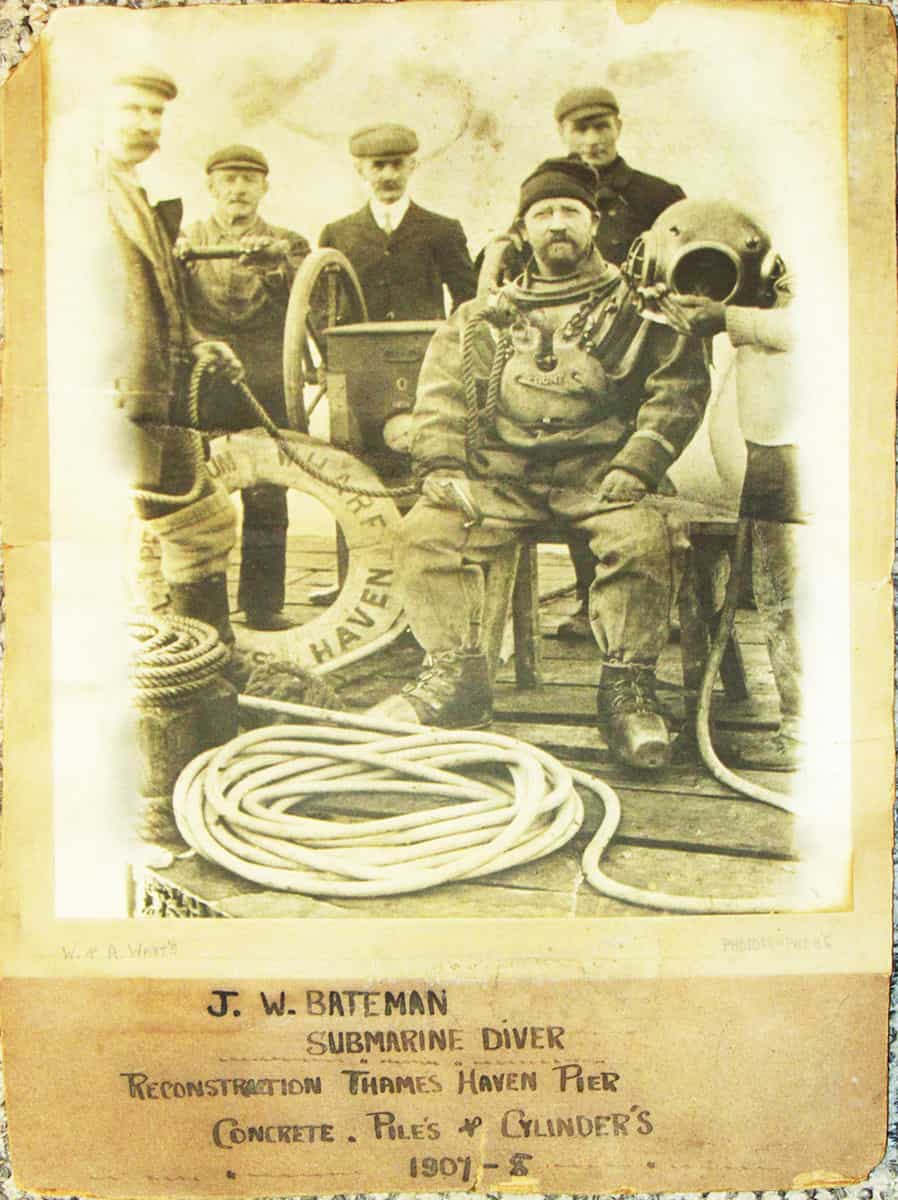

Before Tom Daley, there was Jack ‘Ginger’ Bateman, a celebrity diver in the 1890s and one of those tasked with digging the vast foundations for Tower Bridge deep in the Thames.

Sir Horace Jones’ iconic bascule bridge was designed on a scale never seen before in Victorian times, and its construction alone was a masterful feat of engineering.

Ginger – named thus for his shock of red hair – was part of an elite team of divers who risked life and limb excavating the gravel and clay to secure the foundations for the 70,000-ton bridge some 21 feet below the riverbed.

He had made quite a name for himself as a decorated diver with the Royal Navy, commanding up to £10 per hour underwater – a substantial sum in the 1890s – but, like thousands of others that worked on London’s most famous landmark, his name never made the history books, until now.

Two Towers is a new permanent exhibition in the bridge’s north and south towers that uncovers the lives of the people who designed and built Tower Bridge, as well as those who have been instrumental in its operation over the last 124 years.

The launch marks phase two of a three-year redevelopment of the engine rooms, towers and walkways to share the human history behind the bridge. The engine rooms re-opened in April last year with a permanent exhibition of stories from the coal stokers to cooks, clerks and engineers who worked behind the scenes to keep the bridge in motion.

Now, the north and south towers have been dedicated to the personal histories of the architects, thinkers and makers who were responsible for the construction of the bridge over eight long years, before it was officially opened on 30 June 1894.

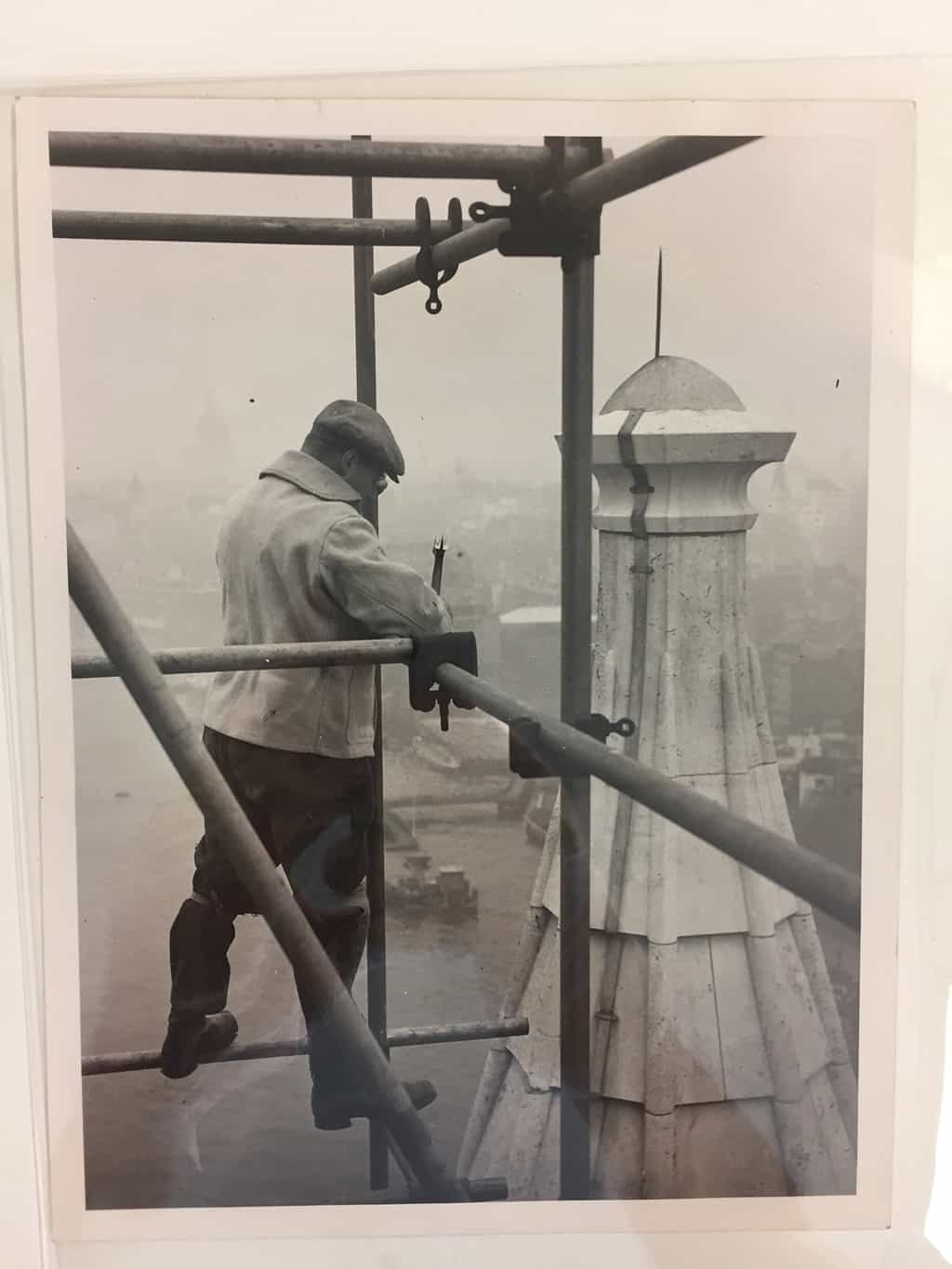

This was a process that required five major contractors, an average of 432 construction workers per day, 11,000 tons of imperial steel and between 13 and 14million rivets, among other mind-boggling facts and figures that have been documented in the exhibition. The question is why, unlike at London’s other tourist attractions, haven’t they been showcased before?

“We have to remember that the bridge was designed as a functional piece of infrastructure, it only became a museum in 1982,” explains Adam Blackwell, who is Tower Bridge’s principal exhibition manager.

“Visitors would be asking questions about who worked here, and what it was like – we didn’t have an archive or really much information at all to work from so we’ve basically had to start from scratch and get the public to help us based on their own family histories.”

That’s how they discovered the story of head diver Samuel Friend Penny, whose great grandson got in touch when he heard about the project, and even managed to produce the gold pen that had been presented to the divers at the opening ceremony by the Prince and Princess of Wales – the future King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. Samuel has been recognised with a commemorative bronze plaque in the South Tower, and a replica of his helmet, which visitors can try on to get a sense of what the job entailed.

“It was dangerous work; it would have been dark, dirty, and their equipment weighed about 90 kilograms, so they really were brave men, which explains why some of them became quite famous,” Adam says.

Other stories chronicled through never-before-seen archive footage, photographs, original objects and interactive displays include those of the workers responsible for fixing around three million rivets by hand, right through to the civil engineer Sir John Wolfe Barry, who oversaw construction after the death of Sir Horace in 1885.

There is also tales from the day-to-day operation of the bridge, like its colour change to the famous red, white and blue for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, and the exceptionally unlucky merchant ship Monte Urquiola that managed to collide with the bridge on three separate occasions over the course of a decade.

“It has been struck a number of times – we’re actually not entirely sure how many – but we believe that’s the only ship that managed it three times,” Adam says.

Work has already begun on developing stage three of the exhibition, which will be housed in the walkways that connect the two towers high above the Thames and is due for completion in 2010.

Exactly what it will look like depends on what else Adam and his team can uncover.

“The bridge has been around almost 125 years so we’re hoping the public can help us with more stories that have been passed down through their families to complete the picture.”

Cover image by Barcex (Creative Commons).